Bayt Nabala

Bayt Nabala

بيت نبالا Bayt Nabala, Beit-Nabbala | |

|---|---|

Former schoolhouse of Bayt Nabala, presently used by the Jewish National Fund in Beit Nehemia | |

| Etymology: "The house of archery"[1] | |

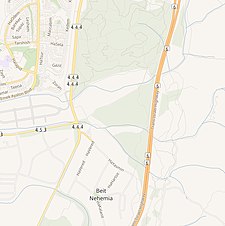

A series of historical maps of the area around Bayt Nabala (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°59′8″N 34°57′24″E / 31.98556°N 34.95667°E | |

| Palestine grid | 146/154 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Ramle |

| Date of depopulation | 13 May 1948[4] |

| Area | |

• Total | 15,051 dunams (15.051 km2 or 5.811 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

• Total | 2,310[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Abandonment on Arab orders |

| Current Localities | Kfar Truman,[5] and Beit Nehemia[5] |

Bayt Nabala or Beit Nabala was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict in Palestine that was destroyed during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The village was in the territory allotted to the Arab state under the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which was rejected by Arab leaders and never implemented.[6][7][8] Its population in 1945, before the war, was 2,310.

It was occupied by Israeli forces on 13 May 1948[4] and was completely destroyed by them on 13 September 1948.[9] Village refugees were scattered around Deir 'Ammar, Ramallah city, Bayt Tillow, Rantis, and Jalazone refugee camps north of Ramallah. Some of the clans that lived in Bayt Nabala include the AlHeet, Nakhleh, Safi, AL-Sharaqa, al-Khateeb, Saleh and Zaid families. Today the area is part of the Israeli town of Beit Nehemia.

History

[edit]

Bayt Nabala is identical with the ancient Beth Nabala/Beth Nablata.[10]

Ottoman period

[edit]

In 1526 Bayt Nabala was part of the Ottoman Empire, nahiya (subdistrict) of Ramla under the Liwa of al-Quds. According to Ottoman tax records, the village paid 500 akçe annually.[11] In the 1596 tax record, Bayt Nabala was categorized under the Liwa of Gaza, with a population of 54 Muslim households, an estimated 297 people. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3 % on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, olives, fruit, as well as on goats, beehives and a press that was used for processing either olives or grapes, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 8,688 akçe.[12]

In the 17th century, the village received an influx of refugees from neighboring Beit Qufa, who had to abandon their home due to unsettled conditions.[13]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Beit Nabala belonged to the Nahiyeh (sub-district) of Lod that encompassed the area of the present-day city of Modi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut in the south to the present-day city of El'ad in the north, and from the foothills in the east, through the Lod Valley to the outskirts of Jaffa in the west. This area was home to thousands of inhabitants in about 20 villages, who had at their disposal tens of thousands of hectares of prime agricultural land.[14] According to historian Roy Marom "Bayt Nabālā was a major hub for the Qays and Yaman conflicts in the area." Bayt Nabala's first residents were the Qaysi "al-Sharāqa" clan. Local tradition holds that a Yamani immigrant called Salām came and camped in the caves near Bayt Nabālā.

When a conflict broke out between Bayt Nabālā and al-Ḥadītha, Salām took advantage of the plight of the residents of Bayt Nabālā to gain control over them, and his three “sons” – Zayd, Nakhla and Ṣāfī – settled in the village. Relations between the clans were strained, and riots broke out between them. A Qaysī leader, named ‘Ābid, from the old al-Sharāqa clan, led his forces and allies, from Jayyūs and Dayr Abū Mash‘al, against the supporters of the Yaman in Qibyā and Dayr Ṭarīf. With the support of the powerful and influential Yamanī families – al-Khawāja from Ni‘līn and the Abu Ghosh family – Ṣāfī succeeded in persuading the authorities to arrest ‘Ābid and eliminate him. Ṣāfī then extended his control over Dayr Ṭarīf, al-Ṭīra, Qūla, Fajja and Mulabbis.[15]

In 1838 Edward Robinson noted Bayt Nabala from the tower in Ramle.[16]

In 1870 Victor Guérin visited and found the village to have about 900 inhabitants.[17] Socin found from an official Ottoman village list from about the same year that Bayt Nabala had 108 houses and a population of 427, though the population count included men, only.[18] Hartmann found that Bet Nebala had 118 houses.[19]

In 1882, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Bayt Nabala as being of moderate size, situated at the edge of a plain.[20]

Since the end of the 19th century, the inhabitants of Beit Nabala cultivated the lands of the deserted village of Jindas.[15]

British Mandate era

[edit]

The school was founded in 1921 and had about 230 students in 1946–47.[21]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Bait Nabala had a population of 1,324 inhabitants; 1,321 Muslims and 3 Christians,[22] increasing in the 1931 census to 1758, all Muslims, in a total of 471 houses.[23]

In the 1945 statistics, the village had a population of 2,310 Muslims,[2] while the total land area was 15,051 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[3] A total of 226 dunums of village land was used for citrus and bananas, 10,197 dunums were used for cereals, 1,733 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[5][24] while 123 dunams were classified as built-up public areas.[25]

-

Bayt Nabala 1942 1:20,000

-

Bayt Nabala 1945 1:250,000

-

Depopulated villages in the Ramle Subdistrict

1948 war and aftermath

[edit]Benny Morris writes that the village residents abandoned it on Arab orders on 13 May 1948. However, according to Walid Khalidi, this cannot be confirmed.[5]

The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the village site in 1992: "The site is overgrown with grass, thorny bushes, and cypress and fig trees. It lies on the east side of the settlement of Beyt Nechemya, due east of the road from the Lod (Lydda) airport. On its fringes are the remains of quarries and crumbled houses. Sections of walls from the houses still stand. The surrounding land is cultivated by the Israeli settlements."[5]

Culture

[edit]According to the Palestinian Heritage Foundation, Beit Nabala dresses (together with those of the village of Dayr Tarif), "were usually done on cotton, velvet or kermezot silk fabric. Taffeta inserts embroidered in Bethlehem style couching-stitch in gold and silk cord were attached to the yoke, chest panel, sleeves and skirt. In the 1930s black velvet material became popular, and dresses were embroidered in couching straight on the fabric with brown or orange couching embroidery which later became famous for this area."[26]

See also

[edit]- Palestinian costumes

- Killings and massacres during the 1948 Palestine war

- Depopulated Palestinian locations in Israel

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 226

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 29

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 66

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. xix, village #222. Also gives the cause for depopulation.

- ^ a b c d e Khalidi, 1992, p. 366

- ^ Rogan, Eugene (2012). The Arabs: A History (3rd ed.). Penguin. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-7181-9683-7.

- ^ Morris, Benny (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9.

- ^ Galnoor, Itzhak (1995). The Partition of Palestine: Decision Crossroads in the Zionist Movement. State University of New York Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-7914-2193-2.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 354.

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1976). "Gazetteer of Roman Palestine". Qedem. 5: 40. ISSN 0333-5844. JSTOR 43587090.

- ^ al-Bakhit, Muhammad Adnan (2011). The Detailed Defter of The Liwāʾ of Noble Jerusalem. al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-78814-642-5.

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 153, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 365

- ^ Marom, Roy (1 November 2022). "Jindās: A History of Lydda's Rural Hinterland in the 15th to the 20th Centuries CE". Lod, Lydda, Diospolis. 1: 14.

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022). "Lydda Sub-District: Lydda and its countryside during the Ottoman period". Diospolis - City of God: Journal of the History, Archaeology and Heritage of Lod. 8: 103–136.

- ^ a b Marom, Roy (1 November 2022). "Jindās: A History of Lydda's Rural Hinterland in the 15th to the 20th Centuries CE". Lod, Lydda, Diospolis. 1: 14.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, p. 30

- ^ Guérin, 1875, pp. 67 ff, 70

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 147

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 138

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 296, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.365

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 365

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p.22

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 18.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 114

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 164

- ^ "Lydda-Ramleh Region, Palestinian Heritage Foundation". Archived from the original on 24 December 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington DC: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

[edit]- Palestine Remembered - Bayt Nabala

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 14: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Bayt Nabala, Zochrot

- Israel campaign throws spotlight on Jewish refugees from Arab lands, 28 September 2012, BBC